turns out i forgot to upload the other midterm i turned in at ucl this semester – please find attached, etc etc.

for reference:

- (when referenced) my two states are china and indonesia.

- this is the marking / grading scheme

- each of the prompts was meant to be written up in a maximum of 500 words

portfolio 1

Political Analysis: Identifying Selectorate Policy Effects

Choose a historical post-war autocratic regime that existed in one of your two states. Your task is to compose a piece of policy analysis examining the impact of institutionalized representation on the economic-policy agenda put in place during the regime’s duration. In other words, how did the composition of the winning coalition shape economic-policy objectives and implementation? If it seems to be relevant in your case, how did the structure of the selectorate and other stakeholder groups affect regime collapse?

Sukarno’s presidency in Indonesia (1949-1965) was backed by an ideologically diverse winning coalition[1], uniting right-wing military factions alongside the communist party PKI under a personalist[2], populist[3], anti-colonialist[4], anti-democratic[5], non-violent[6] and internationally neutralist[7] rule that, with its authoritarian[8] 1959 turn, took the name of Guided Democracy. His regime provides a stark example of how the composition of a winning coalition can significantly shape economic-policy objectives and implementation, ultimately leading to regime collapse.

Sukarno was focused on political and foreign policy goals like anti-colonialism rather than economics. Government budget deficits, overregulation, corruption, and declining exports crippled Indonesia’s economy[9], yet Sukarno, who despised systematic economic study[10], was unwilling to implement reforms. As the economy crumbled, on paper populist Sukarno grew distant from the Indonesian people suffering from food shortages, job losses and rising prices[11]. The military and PKI both jockeyed for economic influence within the coalition, further undermining coherent policy, requiring him to balance his position between the diverse components of his coalition[12].

Sukarno’s need to balance the competing economic priorities of different coalition members resulted in incoherent economic policies that failed to address Indonesia’s deteriorating economy. Military support, in particular, was conditional to constant overspending[13], which detracted from infrastructural investment and, combined with poor harvests, led to food shortages[14]. In addition, the military’s takeover of Dutch companies in 1957[15] only gave it a bigger role in the national economy. Notwithstanding sweeping anti-inflationary measures in 1959, the country suffered from crippling inflation, exceeding 600% annually by the mid-1960s, owing to Sukarno’s reckless printing of money to finance military spending[16].

Escalating tensions between the PKI and military eventually led the coalition to unravel, resulting in Sukarno’s downfall. The PKI’s rapid expansion and proposal for the “Fifth Force” – an armed civilian militia[17] – threatened the military’s monopoly on force[18], and Sukarno’s alignment with China added fuel to the fire, heightening military fears of a communist takeover. These tensions culminated in the failed 1965 “Gestapu” coup by leftist officers allied with the PKI[19]. Major-General Suharto, who led the military’s repression of the coup, effectively seized control of the country, marking the collapse of Sukarno’s regime.

Sukarno’s inability to manage internal tensions and his hands-off economic approach, combined with a lack of coherent policies and failure to unite coalition members behind a common economic program, proved fatal for his regime’s durability. His dependence on an extremely broad coalition limited his margin for political and economic manoeuvres while in power and ultimately meant his demise, once the tensions between opposite extremes within the coalition had grown too large. After the coup, one half of Sukarno’s coalition – the military –side-lined Sukarno in favour of Suharto and crushed the other half, the PKI[20], introducing sweeping economic reforms in the so-called “New Order”[21].

[1] See Nair, D. (2023). Populists in the shadow of great power competition: Duterte, Sukarno, and Sihanouk in comparative perspective. European Journal of International Relations, 13540661231173866.

[2] The speech starting the season of the Guided Democracy directed Indonesians to “bury the parties”. In addition, he is described as having “rousing oratory” and a “deep and electric” relation with his base (Nair 2023). See also the GWF classification. The diverse composition of Sukarto’s winning coalition, in the absence of strong mediating institutions, means his political choices were highly personalised and centralised (Nair 2023, Destradi and Plagemann 2019).

[3] Sukarno presented himself as the “representative of the small people (wong cilik) by positioning himself as the mouthpiece of the Indonesian people (penyambung lidah rakyat Indonesia).” (Okamoto, 2009).

[4] Anti-colonialism, and in particular Sukarno’s “continuous revolution” against neo-colonial powers was a key binding element for the ideologically disparate groups backing Sukarno’s power during the Guided Democracy period (Nair 2023).

[5] Democratic institutions, alongside international élites, constituted the political establishment targeted by Sukarno’s populist critique (Legge 1972).

[6] “Crucially, and despite his vainglory and authoritarianism, Sukarno was not a killer” (Nair 2023). See also the GWF classification, which crucially highlights the lack of violence during the 1965 coup that ended his regime.

[7] His neutralist position caused his regime to be directly targeted by the United States (Kahin and Kahin 1995) and indirectly by the Eastern Bloc’s support of the PKI (Nair 2023). Precisely because of the hostile behaviour exhibited by the United States, which included supporting regional rebellions and the Dutch occupation of Papua as well as attempts to Sukarno’s life, in the lead up to the Guided Democracy Sukarno aligned himself more and more against the West.

[8] With Guided Democracy, Sukarno concentrated executive power, weakened parties, and dismissed the elected parliament (Lev, 1966).

[9] See Tan, T. K. (1967). Sukarnian economics., and Feith, H. (1967). Politics of Economic Decline. in Sukarno’s Guided Indonesia.; Sukarno (Wikipedia).

[10] See Tan, T. K. (1967). Sukarnian economics., and Feith, H. (1967). Politics of Economic Decline. in Sukarno’s Guided Indonesia.; Sukarno (Wikipedia). He instead promoted ideological formulas such as Trisakti (comprised of political sovereignty, economic self-sufficiency, and cultural independence) and Berdikari (indicating Indonesians “standing on their own feet” and achieving economic self-sufficiency, free from foreign influence) (Adams, C. (1980). Sukarno my friend. in Sukarno (Wikipedia)).

[11] See Weinstein (2007), Reinhardt (1971).

[12] Referencing in particular his “withdrawal and return technique” by which he orbited out for foreign travels leaving squabbling politicians to work out his ideas, thus tactfully staying “above” partisan party politics (Legge, 1972: 343). See also Hadiz and Robinson (2017).

[13] See Crouch (1978), Sukarno (Wikipedia).

[14] Sukarno (Wikipedia).

[15] See Lev (1966), Guided Democracy in Indonesia (Wikipedia).

[16] See Thee (2012), Sukarno (Wikipedia).

[17] See Roosa (2006), Zhou (2019), Nair (2023).

[18] “The army sensed a decisive assault on its claim as the sole possessor of coercive power. In the heady political climate of 1965, where questions were being asked of Sukarno’s failing health (he had collapsed at a public gathering), rumors circulated of the CIA grooming right-wing generals to prevent a communist takeover, while the communists were rumored to be secretly negotiating a small arms deal with China for the “fifth force.”” (Nair, 2023).

[19] “The coup plotters sought to pre-empt what they feared was an imminent CIA backed coup by rightwing generals.” (Nair 2023). See also Pauker (1967), Van der Kroef (1973).

[20] While the transition itself was not violent (GWF), Suharto initiated mass killings to destroy the Communist party and the Indonesian left. (Roosa 2006)

[21] See Panglaykim (1967).

Policy Brief: How Can Representation Be Strengthened?

All democracies have face representational challenges. While democratic institutions are intended to improve representation of a population’s political desires over nondemocratic institutions, their configuration shapes the ways in which interests are represented. Likewise, the ways in which political candidates seek to build their bases of support affect the links between voters’ desires and policy outcomes. From your two states, choose one with democratic institutions and propose a reform to improve the representation of voter interests in politics.

Chinese Indonesians have faced institutionalized discrimination and exclusion from the political process for decades. They are a critical point for the country, as highlighted in the 2023 Freedom House report – which states they are poorly represented and little engaged in politics, vulnerable to harassment and affected by unequal restrictions on owning property. To improve their political representation, I propose reforming Indonesia’s citizenship laws to adopt jus soli principles and abolish discriminatory regulations that target citizens of Chinese descent. This reform will promote greater equality and political participation for all Indonesians regardless of ethnicity, consistent with the national motto ‘Unity in Diversity’.

Chinese Indonesians have been historically discriminated, and that has unfortunately continued even after the end of the New Order regime. For instance, Indonesia’s current citizenship laws – based on jus sanguinis principles – impose additional burocratic hurdles for those of Chinese descent to obtain official documents. Discriminatory policies persist at the local and national level; racist incidents still occur in parliament, and local governments continue to target Chinese communities unfairly. This legalized discrimination disincentivises Chinese Indonesians from fully participating politically, perpetuating a sense of marginalization within the broader democratic framework and hampering their ability to influence policy outcomes. Without political power, marginalized groups cannot advocate effectively for their interests in the policymaking process.

The proposed reform would amend discriminatory statutes and strengthen the citizenship law to ensure equal rights for all Indonesian citizens, irrespective of their ethnic background. This reform aims to eliminate legal barriers that impede the full participation of Chinese Indonesians in political processes. To address this, I propose reforming the citizenship law to abolish differentiation based on ethnicity. The new law should adopt jus soli principles, granting citizenship to all born within Indonesia’s borders regardless of parentage or background. Chinese Indonesians would then gain equitable access to identity documents, removing a key obstacle to political participation. They will be empowered to fully exercise their democratic rights; their representation will grow, channelling their voice and interests in policy fora.

This reform can be implemented by introducing new legislation in parliament. The law should have support from mainstream parties with strong Chinese representation like PDI-P. Coalition-building with moderate Muslim groups will also be critical to create cross-ethnic backing. Chinese NGOs and civil rights groups can mobilise public pressure, specifically around Sinophobia and in response to the growing relevance of extreme Muslim populists, known to target Chinese Indonesians. Passing this reform faces challenges from conservative élites contrary to sharing power, which is why strong civil society advocacy and support from progressive parties is key to the passing of this reform. The long-term stability and quality of Indonesian democracy depends on extending equal rights to all citizens, not just the majority. This reform will complete the political participation reforms initiated after the fall of Suharto’s regime, bringing lasting benefits for Chinese Indonesians and Indonesia as a whole.

How Does Public Opinion Influence Your Foreign-Policy Menu?

The relationship between public opinion and foreign policy has received renewed attention from international relations scholars and political economists over the past decade or two. Choose one of your states and research current public opinion on regional issues. How are these likely to shape the government’s policy choices over regional coordination and cooperation in the immediate and near future?

It is tempting to question the relevance of public opinion in determining Chinese politics. Although Chinese leaders are not formally tied to public opinion[1], the public’s support remains a strong incentive[2], particularly as a legitimising factor in matters of sovereignty and territorial integrity[3]. An overview on poll results concerning two highly contentious foreign policy issues – a possible invasion of Taiwan and the territorial disputes in the South China Sea – shows the complex interplay of nationalist fervour and pragmatic considerations shaping Chinese public opinion.

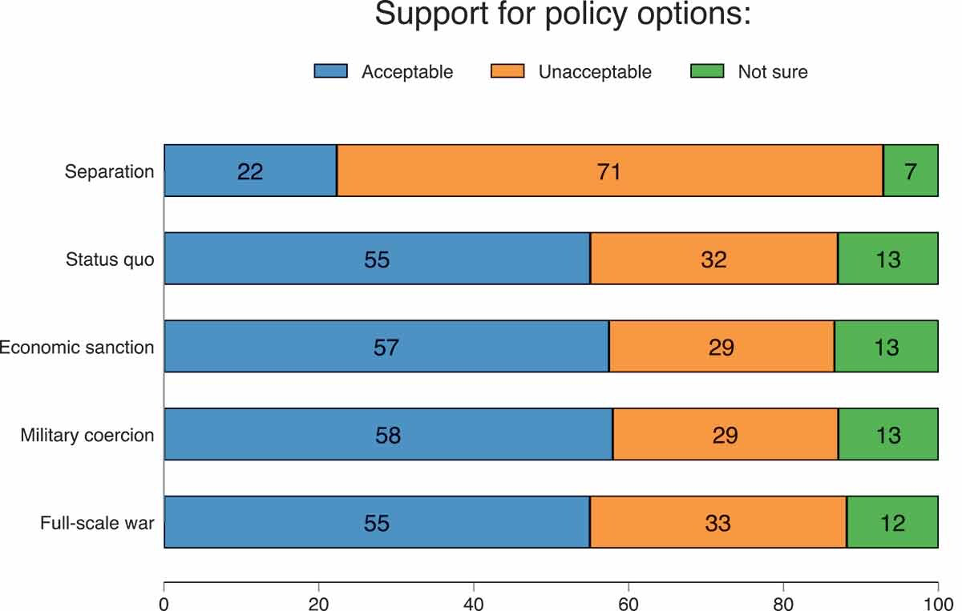

Taiwan represents a deeply sensitive issue for the Chinese public, owing to sentiments of national pride and historical identity[4]. However, a recent survey[5] paints a more nuanced picture, challenging the notion of overwhelming support for immediate military action. While a majority favours eventual unification, only 55%, driven by nationalism and peer pressure, endorse armed unification; while others, more sensitive to the economic, human, and reputational costs of war – as well as the perspective of US intervention – prefer diplomatic engagement or the status quo. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), often portrayed as dependent on defending territorial integrity for its legitimacy, may then have more leeway to relax its aggressive posturing against Taiwan without generating an overwhelming backlash undermining its legitimacy.

Despite framing the issue under the lens of national humiliation[6], Chinese public sentiment on the South China Sea exhibits a pragmatic disapproval of kinetic escalation. While symbolic gestures of sovereignty garner public support[7], there is a simultaneous recognition of the economic and diplomatic value of stability. While surveys reveal an inflated confidence in China’s legal claims[8], analysis of exemplary cases concerning China’s on-water assertiveness does not indicate strong bottom-up influence on government policy in the area[9]. Thus, the government is afforded flexible options to manage tensions below the threshold of military clashes, utilizing nationalist rhetoric to satisfy public opinion without escalating into open conflict.

In both Taiwan and the South China Sea, Chinese public opinion proves more nuanced than often portrayed, with nationalism often tampered by pragmatic considerations. While the CCP’s legitimacy, hinges on projecting strength on these territorial issues, it is provided room for calibrated escalation, enabling a careful balance between public sentiment and diplomatic manoeuvring. Despite the challenges posed the CCP’s black box élite politics and its insulated media environment, the findings indicate a degree of flexibility in navigating complex regional challenges beyond nationalist escalation, while also highlighting the government’s relative independence from public opinion in some relevant cases[10].

[1] Chubb, A. (2019). Assessing public opinion’s influence on foreign policy: the case of China’s assertive maritime behavior. Asian Security, 15(2), 159-179.

[2] Debs, A., & Goemans, H. E. (2010). Regime type, the fate of leaders, and war. American Political Science Review, 104(3), 430-445.

[3] Downs, E. S., & Saunders, P. C. (1999). Legitimacy and the limits of nationalism: China and the Diaoyu Islands. International Security, 23(4), 114-146.

[4] Sinkkonen, E. (2021). The role of the Taiwan question in Chinese national identity construction. In Taiwan (pp. 1-17). Routledge.

[5] Liu, A. Y., & Li, X. (2023). Assessing Public Support for (Non-) Peaceful Unification with Taiwan: Evidence from a Nationwide Survey in China. Journal of Contemporary China, 1-13.

[6] See Chubb, A. (2014). Exploring China’s” Maritime Consciousness”: Public Opinion on the South and East China Sea Disputes.

[7] See Weiss (2021); Medcalf & Heinrichs (2011).

[8] See Weiss (2021

[9] See Chubb, A. (2021). Chinese Nationalism and the “Gray Zone”: Case Analyses of Public Opinion and PRC Maritime Policy. Naval War College Press.

[10] “The new and expanded on-water actions examined here are among the most directly consequential aspect of China’s current maritime policy, and these appear to have had little or nothing to do with public opinion.” (Chubb 2019)

Bibliography

prompt 1 – references

Anderson B (2009) Afterword. In: Mizuno K and Pasuk P (eds) Populism in Asia. Singapore: NUS Press and Kyoto University Press, pp. 217–220.

Aslanidis P (2021) Coalition-making under conditions of ideological mismatch: the populist solution. International Political Science Review 42(5): 631–648.

Crouch H (1978) The Army and Politics in Indonesia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Destradi, S., & Plagemann, J. (2019). Populism and International Relations:(Un) predictability, personalisation, and the reinforcement of existing trends in world politics. Review of International Studies, 45(5), 711-730.

Feith H (1962) The Decline of Constitutional Democracy in Indonesia. Ithaca, NY. Cornell University Press.

Feith, H. (1967). Politics of Economic Decline.”. Sukarno’s Guided Indonesia.

Glassburner, B. (1962). Economic policy-making in Indonesia, 1950-57. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 10(2, Part 1), 113-133.

Hadiz V and Robison R (2017) Competing populisms in post-authoritarian Indonesia. International Political Science Review 38(4): 488–502

Kahin A and Kahin GT (1995) Subversion as Foreign Policy: The Secret Eisenhower and Dulles Debacle in Indonesia. New York: New Press

Legge J (1972) Sukarno: A Political Biography (3rd edn). Singapore: Archipelago Press

Lev D (1966) The Transition to Guided Democracy: Indonesian Politics 1957–1959. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Nair, D. (2023). Populists in the shadow of great power competition: Duterte, Sukarno, and Sihanouk in comparative perspective. European Journal of International Relations, 13540661231173866.

Okamoto M (2009) Populism under decentralization in post-Suharto Indonesia. In: Mizuno K and Pasuk P (eds.) Populism in Asia. Singapore: NUS Press in association with Kyoto University Press.

Panglaykim, J., & Thomas, K. D. (1967). The New Order and the Economy. Indonesia, (3), 73-120.

Pauker, G. J. (1967). Indonesia: the year of transition. Asian Survey, 138-150.

Reinhardt, J. M. (1971). Foreign policy and national integration: the case of Indonesia. (No Title).

Roosa J (2006) Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup d’etat in Indonesia. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Solingen E and Gourevitch PA (2018) Domestic coalitions: international sources and effects. In: Thompson WR (ed.) The Oxford Encyclopedia of Empirical International Relations Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tan, T. K. (1967). Sukarnian economics. Sukarno’s Guided Indonesia, 29-45.

Thee, K. W. (2012). Indonesia’s economy since independence (Vol. 35). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Van der Kroef, J. M. (1973). Sukarno’s Indonesia. Pacific Affairs, 46(2), 269-288.

Weinstein, F. B. (2007). Indonesian foreign policy and the dilemma of dependence: From Sukarno to Soeharto. Equinox Publishing.

Wikipedia – “Guided Democracy in Indonesia” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guided_Democracy_in_Indonesia

Wikipedia – “Suharno” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sukarno

Wikipedia – “30 September Movement” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/30_September_Movement

Zhou T (2019) Migration in the Time of Revolution: China, Indonesia, and the Cold War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

prompt 2 – references

Freedman, A. (2003). Political institutions and ethnic Chinese identity in Indonesia. Asian ethnicity, 4(3), 439-452.

Freedom House (2023). Indonesia: Freedom in the World 2023 Country Report.. https://freedomhouse.org/country/indonesia/freedom-world/2023

Hatherell, M. (2019). Political representation in Indonesia: The emergence of the innovative technocrats. Routledge.

Hoon, C. Y. (2006). Assimilation, multiculturalism, hybridity: The dilemmas of the ethnic Chinese in post-Suharto Indonesia. Asian Ethnicity, 7(2), 149-166.

Ling, C. W. (2014). Democratisation and Ethnic Minorities: Chinese Indonesians in Post-Suharto Indonesia.

prompt 3 – references

Chubb, A. (2014). Exploring China’s” Maritime Consciousness”: Public Opinion on the South and East China Sea Disputes.

Chubb, A. (2019). Assessing public opinion’s influence on foreign policy: the case of China’s assertive maritime behavior. Asian Security, 15(2), 159-179.

Chubb, A. (2021). Chinese Nationalism and the “Gray Zone”: Case Analyses of Public Opinion and PRC Maritime Policy. Naval War College Press.

Debs, A., & Goemans, H. E. (2010). Regime type, the fate of leaders, and war. American Political Science Review, 104(3), 430-445.

Downs, E. S., & Saunders, P. C. (1999). Legitimacy and the limits of nationalism: China and the Diaoyu Islands. International Security, 23(4), 114-146.

Liu, A. Y., & Li, X. (2023). Assessing Public Support for (Non-) Peaceful Unification with Taiwan: Evidence from a Nationwide Survey in China. Journal of Contemporary China, 1-13.

Medcalf, R., & Heinrichs, R. (2011) Crisis and confidence: major powers and maritime security: Major Powers and Maritime Security in Indo-Pacific Asia. Lowy Institute for International Policy. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/pubfiles/Medcalf_and_Heinrichs,_Crisis_and_confidence-revised_1.pdf

Sinkkonen, E. (2021). The role of the Taiwan question in Chinese national identity construction. In Taiwan (pp. 1-17). Routledge.

Weiss, J. C. (2021, December 7). Here’s what China’s people really think about the South China Sea. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/07/14/heres-what-chinas-people-really-think-about-the-south-china-sea/

feedback

Part 1 (80)

This analysis of Sukarno’s support base does a good job of demonstrating the effects that jockeying between rival groups had on economic policy.

There is, potentially, a question about the formation of the winning coalition versus the overall selectorate, given the extent of concessions made to military leadership and its influence on policies. The potential uncertainty around this is dealt with quite well through the use of academic sources and in the footnotes.

Overall, this is an impressive composition and a superb example of analytical work.

Part 2 (65)

This brief argues for a clearer pathway to citizenship for Chinese Indonesians. It makes a fairly compelling case for what would be a significant legal reform to Indonesia’s treatment of citizenship.

However, there is no direct engagement with the relevant academic or policy literature, and required citations, where factual information is presented, are absent (in addition to the incomplete reference to a Freedom House report). Reference to the literature would be useful for clarifying inequalities in citizenship eligibility, potential bases of support for reform, as well as the treatment of representation itself. On this last point, representation seems to be treated as an ethnic or physiological matter up through the final paragraph, where it is vaguely tied to issues; a look at the literature on types of representation would be worthwhile here.

Structurally, this is well done and nicely organized. However, as a policy brief, it would be more effective to point directly to specific evidence in support of the argument for reform.

Part 3 (70)

This analysis discusses Chinese attitudes on Taiwan and the South China Sea. It does a nice job of framing a recent set of results with China’s foreign-policy agenda on territorial issues.

It would be worth considering the feedback loop in which elites influence opinion, particularly because the Xi administration has employed this top-down mechanism on related issues. It might also be beneficial to consider the framing of this issues – the prompt discussed prospects for regional cooperation and coordination, not conflict.

Overall (72/100)

This is generally a very strong set of compositions. The first component is the strongest, while the second lacks appropriate referencing and would benefit from deeper engagement with the relevant literature. The final component is nicely written, but could more directly respond to the prompt as well as provide a more detailed consideration of the interactions between CCP leadership and mass attitudes. Overall, this is a very good portfolio.