from the beginning of the [latest phase of the] ru-ua war, it seemed clear to me that the it army of ukraine constituted a fascinating phenomenon, sitting at the intersection of a few very hot topics:

- state actors acting in cyberspace

- cyberwar, however you want to define it

- the application of public international law in cyberspace

- cyber theory (what if attribution was certain?)

- the meaning of categories like “civilian” and “combatant” in cyber

- a literal active international conflict

and more.

of course, as of publishing this, the issue is still developing, and a lot of very good analyses have been put out since those early days. I myself did a lot of data collection, and started analysing that data – then stopped collecting as my second analytical foray into this topic was going nowhere and I had to graduate my Bachelor’s. Fun fact: I actually considered writing my thesis on this topic, but my supervisor and I both agreed it would have been very bad taste.

anyways, all the way back on March 9th, 2022, I participated in an international law seminar with a five minutes long contribution, which I am posting here as the first step in my reflections on this topic.

and here’s a transcript of the whole thing.

Prof. Andreas de Guttry: Thank you, Baldini. Now, the next intervention will be on a very recent problem, namely the so-called “IT Army” to be used during warfare – Pagnacco, you have the floor.

me: So, I wanted to thank Prof. de Guttry, all participants, and all attending, and very briefly move to some recent developments in the present conflict in cyberspace. Now, reported Russian activity in cyberspace is coherent [consistent, sic] with traditional cyberwarfare techniques, and the Ukrainian government and organisations are more than accustomed to this kind of threat. But what is surprising, and what is interesting, is the nature of the response that has been quickly implemented by Ukraine.

So, as we can see… [technical issues with slides changing]… I don’t think we can see it anymore, but there was a tweet, and it was the announcement of the creation of a group called the IT Army of Ukraine, that entails public, mostly offensive operations sanctioned, or even incited, by a current member of the Ukrainian government, against its enemy in an active international armed conflict. And we see a call to voluntary participation of foreigners, which is facilitated by the translation in English of some of the tasks that are requested of these volunteers. These include DDoS attacks, system intrusions, or doxing, and they are all targeted towards media organisations, government officials or, in any case, Russian targets.

Somewhat cleverly, those actions currently fall below the threshold to be considered cyberattacks in terms of effects. For the definition of cyberattacks, and all further definitions, I will be referring to the Tallinn Manual 2.0, which is a non-binding, NATO-aligned scholarly work, in absence of binding agreements and/or consolidated precedent.

So, for ius in bello, the Tallinn manual posits that, in fact, IHL [International Humanitarian Law, aka Law of Armed Conflict] also applies in cyberspace, and we see that these new modes of conflict allow for the participation of categories that might not have been able to participate in other forms of hostilities. So we see civilians, we see foreigners, and we see people that are not currently located in Ukraine.

So, my question is: can we configure these civilian participants as participants to a levée en masse, and therefore protected under IHL?

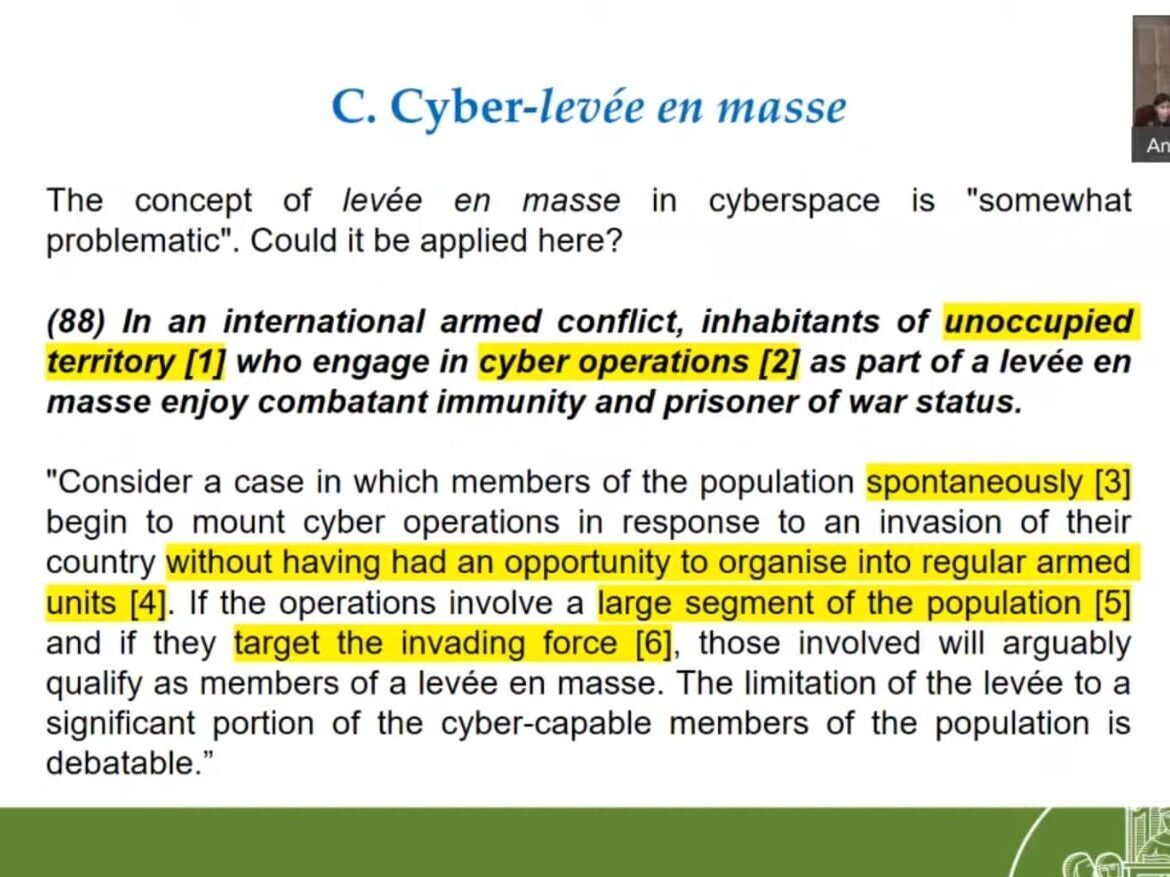

I wanted to analyse Rule 88 of the Tallinn manual, which tries to analyse the concept of levée en masse in cyberspace, and I have highlighted six critical points [in this article].

The first one is the issue of unoccupied territory: so, it is not clear whether in this case it would exclude Ukrainian citizens participating in the hostilities while being physically in a space that is occupied by Russian forces, or whether, on the other hand, it would include foreigners – international citizens – that are in spaces [physically outside of Ukraine] unoccupied by Russian forces and that are fighting for the Ukrainian side.

The second point talks about cyber operations; so it does not exclude operations that do not rise to the level of cyber attacks, we are in the clear there.

The “spontaneously” part is interesting, because clearly there are commands, and these commands are being transmitted completely via a Telegram channel; but these can be equated to “orders given over the wireless” and therefore [they] wouldn’t exclude a levée en masse, per se.

The fourth point on the opportunity to organise – clearly, Ukrainians have had the opportunity to organise in regular kinetic forces, but not so in cyberspace; so it would still remain a possibility,

It is impossible, however, to quantify the segment of the population that is participating in these hostilities, and it is especially hard to determine whether international participants would count towards that quota.

And finally, it is unclear whether it is necessary that these activities must target the invading force per se, and not, in general, the enemy – so, generally speaking, Russian targets.

So I think there is a lot of space for further discussion on this topic, but I will leave the floor to Vincenzo [the following speaker]. Thank you.

AdG: Thank you Anna, I think that you have raised a very innovative aspect, which probably will become more and more popular – and therefore this is a good argument which might need to be further analysed and investigated.